Exposed: the tactics behind professional search results burying

It’s one of the realities of the digital age: once something’s on the internet, it’s almost impossible to erase.

We’ve all Googled our own name, and maybe there’s something in the search results you’d rather didn’t appear - an unflattering headshot, say, or a Myspace profile you can’t log into to get rid of. Personally it’s a photo of me in a Thomas the Tank Engine vest which is one of the first image results for my name due to an ill-advised headshot submission during peak lockdown mania.

While most would accept this as something unchangeable, there’s a nefarious underground industry of professional search results buriers who take on jobs for people who have much bigger problems to hide.

In February The Guardian published a fascinating exposė on one such company, who’ve been described as “a reputation laundromat for criminals.” Their clients allegedly include money-launderers, hitman-hirers and sex offenders, all of whom are willing to pay large sums to cleanse the search results of news reports of their crimes.

So how do they go about hiding these results?

The first thing to note is that SEO is actually a last resort for this group. As reported by The Guardian, initial tactics include trying to trick news sites into removing articles about their clients by spoofing the email addresses of major news corporations and claiming copyright of the original article, or producing a backdated version of the same piece and submitting copyright infringement claims to Google.

But when that doesn’t work, they’re forced to try and flood the search results with other content which will bury the harmful articles. Understandably, The Guardian weren’t particularly interested in the finer SEO tactics being used, so this is the key part of the story that has remained missing - until now. With some help from the Evoluted SEO team, I’ve gone digging to lift the lid.

The network effect

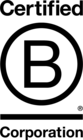

A key weapon in hiding the undesirable results is an enormous network of domains owned by this company: an investigation by Qurium found 622 sites, to be exact, each purporting to be a legitimate news outlet across a wide array of countries and languages. Faux news sites is a clever move - they can write fake articles about their customers, hoping Google will rank this apparent fresh news coverage above the damaging results they’re trying to displace.

But that still leaves a bigger question: how do they rank these sites in the first place to compete against actual news organisations?

A cursory glance over a selection of the domains on Qurium’s list shows the content quality is (pardon the pun) nothing to write home about. The “articles” are largely nonsense amalgamations of scraped content pieced together from various sources, as in the image below. Some domains switch language from story to story - presumably an oversight as each site purports to be a national news outlet.

In short, content isn’t the reason these sites rank - so it must be their backlinks. Burying search results from genuine news websites requires significant backlink profiles, so where do they get them from?

Clearly, these sites aren’t going to have a loyal readership sharing their content and they’re not going to earn links naturally from people citing their stories as sources.

So what’s their linkbuilding strategy?

The obvious answer would be a Private Blog Network (PBN) - an interconnecting maze of links between the 622 domains which give each a considerable backlink profile and elevate all sites in their network to near the top of search results. While Google’s got better at spotting and delisting these once-powerful arrangements in recent years, they’re still prevalent and can sometimes go years without being spotted.

But a PBN isn’t the answer here. We didn’t find any evidence of links between any of these domains - the first clue that the results-hiders are well-versed in SEO (or more specifically, ‘Black Hat SEO’, the underhand tactics that take a blowtorch to Google’s best practice guidelines). Presumably they realised a PBN would be too obvious and would get them penalised.

That meant we’d have to get more granular to understand what was fuelling these sites’ SEO strength. We took a deep dive into three of the 622 domains, analysing their backlink profiles to understand where their links come from and how they’ve got them.

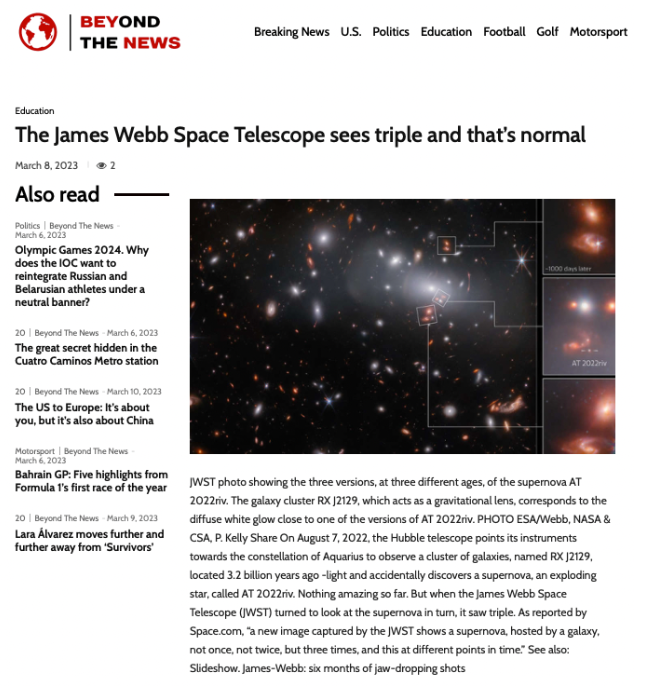

All three domains were only launched in late 2021 but have each already accrued huge backlink profiles of around 7,000 links from over 2,200 different domains. That means the tactics we’ve uncovered have been used within the last 24 months and represent an active black-hat linkbuilding strategy.

Handily, the patterns and tactics are identical across each of the three domains - why change a winning formula?

Strap in - ‘cos it’s wild!

The strategy

The theory underpinning the group’s backlink strategy is the more authoritative the domain, the more valuable the backlink. That’s something of a half-truth these days given it ignores relevancy, like getting links from domains with the same country’s domain extension (ccTLD - e.g. a French site earning links from other .fr domains) or other news sites.

While the authority logic is a bit outdated, it explains each of the categories of link we’ll explore in turn, progressing from least to most outrageous.

First up, old-school directory-style links make up a reasonable part of the backlinks. We’re talking bio links from Buzzfeed user profiles, Creative Commons publisher profiles and Microsoft Developer Network profiles. While these links are unlikely to move the needle much, maybe they add a small amount of legitimacy for search engines.

Even more old-school is forum spam. We found one thread on a University of Arkansas Paralegal Club forum (because university sites = automatic authority, right?) which ran to over 1,700 pages of link spam, all of it almost certainly doing nothing for SEO purposes.

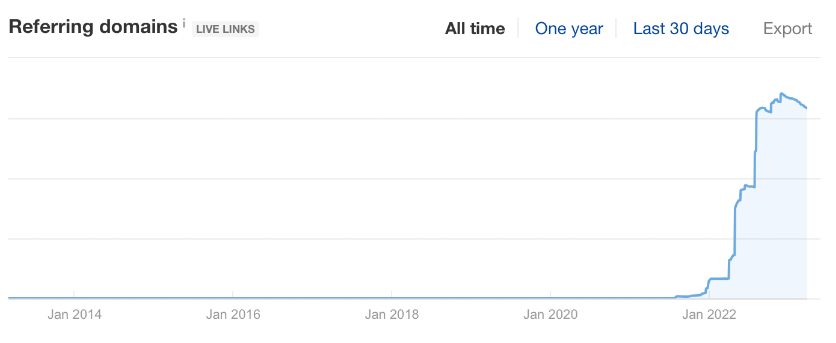

In the same category are links from CGI-bin pages (folders which house scripts on websites). CGI-bins are notoriously vulnerable to being exploited by hackers who can inject their own code to them - especially if the page’s setup is outdated (that’s significant and something we’ll come across again later).

Each of the sites we analysed had gained CGI-bin links from over 100 different domains. In most cases they had added a simple script to a site’s CGI-bin to auto-forward clicks to one of their own domains.

Government links

Remember we started off by establishing their strategy was to target links from as high-authority domains as possible? Well, this is where they take that idea to the absolute extreme.

We found links to the group’s sites from a shocking seven countries’ official government websites - including the UK and US governments plus others in Europe, Asia and Africa.

Clearly, no official site is going to link to some spammy content factory. So the group has to have placed the links there themselves - pretty audacious, right? You’d imagine government websites are about the most secure around, so how have they done this?

The simple answer is they’ve identified weak spots in these domains - legacy parts of high-authority websites where defences are weaker, content is no longer actively updated and where injecting a link will take longer to be discovered.

For example, one of their .gov.uk links comes from a microsite monitoring River Thames conditions; while the site appears to have been updated until 2022, its footer still gives the copyright year as 2008, so it’s probably safe to say it received minimal security attention beyond that point.

Mostly the government links take the form of open redirect manipulation, where attackers can change the destination URL of a link on a legitimate site - and in some cases it’s remarkably easy to replicate it yourself. We found one US government microsite, for the Institute of Education Sciences, where the destination link can be edited in the URL to create a backlink to wherever you’d like - as shown below (I figured my football team, Torquay United, could use all the help they can get at the moment, on and off the field).

Presumably the results-buriers have figured out a way of scraping these kinds of pages en masse, as stumbling across them manually would be like finding a needle in a haystack.

The scraping theory is given credence by some of the other domains in the network’s backlink profile which are an incredibly random assortment of high-authority websites including Ford, Southampton University and the American Cancer Society (hacking a cancer charity for SEO benefits has to be about as low as you can get). These are also obtained through open redirection manipulation.

It seems clear the hackers have deliberately targeted retired or barely supported subdomains where defences are weaker and changes would take a long time to be noticed - if at all. The Ford backlinks, for example, came from a subdomain for a resource hub on servicing their vehicles which Ford had decommissioned and retired from the public.

Missed opportunities

Given the purpose of each site in the group’s network is to pump out fake articles about their clients, and that through their linkbuilding tactics they can control exactly where the links go, you’d have thought they’d build them directly to their “money pages” - the ones they’ve actually written about their clients, rather than the scraped news articles or their homepage.

But strangely the vast majority of backlinks go to either the homepage or quasi-category pages; very few go to specific articles. Maybe that’s because they don’t want to draw attention to them, but it does limit the SEO impact of these links.

It’s also strange they didn’t try and match backlink targets to that domain’s ccTLD - e.g. focusing on building links from French domains to their French news site, which would surely move the needle faster than high-authority links in random languages.

Postscript

While writing up this article I realised across the three domains we’d analysed, the number of indexed pages had suddenly dropped to zero.

For two of them, this could have been explained by the group removing all news articles, leaving just skeleton category pages with no content:

Even then, though, the homepage and category pages remain indexable - so they should show up on a site: search, but they don’t.

The third site we looked at still has all 182 pages of its spammy articles live - but not a single one of those is indexed, either.

So the likelier explanation is that Google has finally caught up with the group after the publication of The Guardian expose - and, just as significantly, the list of all domains associated with the group published by Quirium.

At the time of writing each of the sites in the group’s known network has vanished from search results. The fact the number of indexed pages dropped to absolute zero, rather than declining slowly as it might with a standard organic problem with the site, strongly suggests this is the result of a manual penalty from Google which has blacklisted the sites from search results.

Penalties can be overturned on appeal if the site owner can demonstrate they’ve reversed the spammy activities that caused it - we’ve done so for clients ourselves who came to us with legacy penalties from previous activity.

But in this case we won’t be holding our breath on an overturning. For now, it seems these search results buriers have been buried themselves.

If you are looking to bury some (non-criminal) search results, it’s one of the few times you’d be well-advised to take a leaf out of Boris Johnson’s book - the former PM’s been known to use carefully-placed lines in interviews to displace previous damaging news stories. There’s even a conspiracy theory Taylor Swift’s recent attendance at a New York Jets game was to displace reports on her air miles.

But if you don’t have the luxury of the world’s media hanging on your every move, the Thomas the Tank Engine vest pic is probably staying put.